Camera Ethnography

Over the last decades, camera ethnography has evolved into an independent strand of media ethnography that shows rather than tells. Camera ethnography shifts the emphasis of research from the linguistic to the performative and introduces a mode of perceiving and knowing that unfolds as much between as within images, sounds, words, and audiences’ gazes. At the same time, it offers a practicable methodology that is inherently critical of representationalism and is conceptualized as a continuous reflexive process of working on visibility and seeing.

Filming as an epistemic practice

In our everyday use of media, we take it for granted that we can capture anything with a camera and share it. However, if we assume that the goal of research is to go beyond our current state of knowledge and to see what we have not yet seen, then we are dealing with epistemic things that are not yet immediately visible and hence cannot simply be recorded with a camera. This conclusion draws upon laboratory studies of the sociology of scientific knowledge in the 1980s and 1990s and takes a marked departure from strategies of camera usage that assume visibility exists a priori. The premise of non-visibility has been a fundamental guiding principle in the development of camera ethnography as a methodological approach that aims to bring forth rather than to represent.

Spaces of possibility

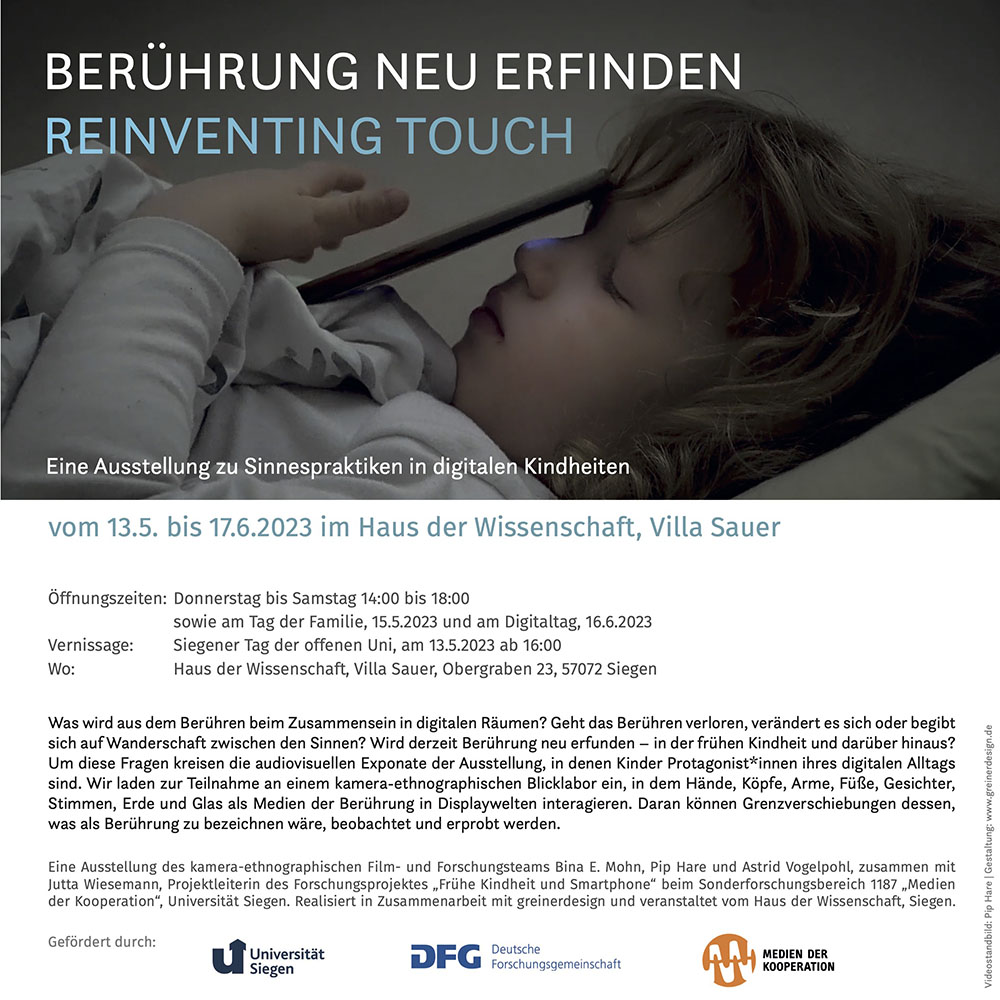

Camera ethnography works towards the thick showing (cf. Geertz’ thick description) of everyday worlds and lends itself particularly well to the study of nonverbal practices and their bodily and material dimensions. Furthermore, camera ethnography is particularly suitable for implementation of Wittgenstein’s “übersichtliche Darstellung” research format: filmic arrangements together with thought provoking interventions serve as an attempt to explore how social practices can be lived, named, and understood – not just here and now, but also there and then. This offers audiences of camera ethnographic research an opportunity to make unexpected discoveries about the diversity and potentiality of social phenomena and practices.

Reception as research

Camera ethnographic productions are presented publicly, inviting audiences to contribute their own perspectives and ways of looking and seeing. Emphasizing this, reception events can be conceptualized as public Blicklabore (laboratories of gazes). Reception means a co-creation of research: gazes interfere with and bring forth what is seen. But whose gazes? What perspectives are at play when the camera ethnographers’ filmic results are observed by diverse viewers? Wittgenstein’s enduring question of how else it could be can be extended to ask: “What further views and perspectives might be imaginable?” Thus, reception events are not simply situations for individual, simultaneous viewing but occasions for collective reflection, shared knowledge, and public debate.

Important influences that have inspired the development of camera ethnography include Bruno Latour (on science-in-the-making), Karin Knorr-Cetina (on epistemic cultures), Hans-Jörg Rheinberger (on experimental systems), Clifford Geertz (on thick description), Ludwig Wittgenstein (on language games and “übersichtliche Darstellung”), and Karen Barad (on agential realism and intra-action).

Where field and research intersect, as well as at the interface of research results and their reception, differently situated practices interact productively. Ethnography can be understood as heterogeneous cooperation; in situated processes of knowledge production, visibility and ways of seeing can be shared and are in perpetual flux.